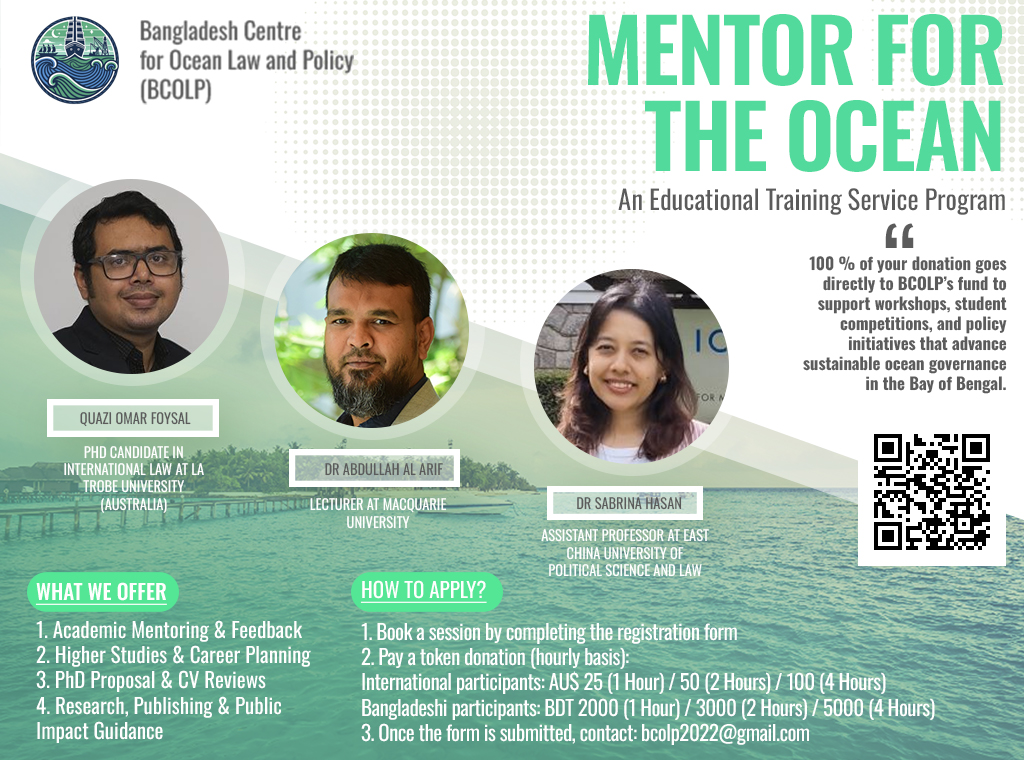

Dr Sabrina Hasan

The evolution of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS) has gained global attention as it is poised to bring significant changes to the maritime industry in every aspect. It is expected that the adoption of autonomous technologies could offer considerable benefits, including safer and more environmentally friendly shipping. However, legal challenges may arise due to incompatibility with the existing laws concerning the rights and duties of states. These challenges may create dichotomies in enforcing jurisdiction over MASS under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)(1). This write-up addresses the challenges that Bangladesh would face as a coastal, port, and flag State when enforcing its jurisdiction over MASS under the law of the sea, and outlines the need for new rules and standards for the regulation and enforcement of jurisdiction over MASS. The role of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) as an international shipping regulatory body and its mandate in addressing these challenges are also crucial to this issue.

To regulate MASS under the existing shipping regulations, it is important to address and identify MASS as a ship within the international legal framework (2). This is a significant challenge to consider MASS as a ship due to its level of automation and other features that are different from conventional ships. There are different types of “crafts” which might not seem like ships in the general sense. However, international standards, requirements, and interpretation of legal provisions do accommodate such ships. Similarly, in a general sense, MASS might not seem to be a ship. Nevertheless, a certain category of MASS depending on the degree of autonomy might be identified as a “ship” (3).

MASS, if considered as ships operating autonomously, must adhere to the same maritime and navigational laws that apply to all other vessels navigating within the waters of the respective jurisdiction. These laws govern the licencing of operators, the registration of vessels and navigation regulations. Regarding the jurisdictional issues, flag states jurisdiction is the cornerstone of shipping regulations (4). To identify the jurisdiction of the states over MASS, the first step is to look into UNCLOS. As per the UNCLOS, to exercise jurisdiction over ships, a flag State must first confer nationality on the ships concerned through the registration process, which confers the right to fly its flag (Article 91(1)). In particular, Article 94(3) requires flag States to take the necessary measures to ensure safety at sea. These measures include, among other things, ensuring the seaworthiness of ships (Article 94(3)(a)) and the manning of ships (Article 94(3)(b)).

Therefore, to register MASS in Bangladesh, the country needs to follow international rules and standards. IMO has categorised the autonomy level of MASS into four degrees (5). Among the four degrees, degree three and degree four are subject to the discussion of non-compliance with UNCLOS provisions that require the manning of ships. Furthermore, Part IV of the Bangladesh Merchant Shipping Ordinance 1983 deals with the requirement of “manning of ships”. As per Section 82 (1) of the 1983 Ordinance, “no ship shall go to sea or proceed on a voyage unless it is manned in accordance with the provisions of this chapter …”. Therefore, the mandatory requirement of manning ships would be a challenge to MASS regulation. In this respect, suggestions have been put forward by academia to apply the “constructive and consistent” interpretation method (6). However, in the case of fully autonomous ships, the suggestions to apply constructive and purposive interpretation methods might not suffice due to the complexity of autonomy and the absence of a human element. The requirements to ensure the manning of ships and the duties concerning masters and crews on board will have a drastic change in respect of fully autonomous ships, thus, becoming incompatible with the existing laws. As a result, determining accountability and responsibility for accidents or incidents involving fully autonomous ships may prove challenging.

As a coastal state and port state, Bangladesh may face some technical and operational challenges in monitoring, inspecting and controlling MASS, such as onboard activities, inspection, and communication on boards (Article 218 of UNCLOS) (7). Certain progress could be seen within the Territorial Waters and Maritime Zones (Amendments) Act 2021. Section 3A of the Act identifies underwater vehicles including remotely operated underwater vehicles, autonomous underwater vehicles and unmanned underwater vehicles with regard to rights of innocent passage in the territorial sea. However, these underwater vehicles are not likely to be considered as ships whereas MASS are, and the regulation of MASS would be different considering the enforcement of jurisdictions over ships especially as a coastal state in respect of passage rights (e.g., Articles 17, 21 and 38 of UNCLOS) (8).

UNCLOS further adds that in taking measures, each State must comply with generally accepted international standards, procedures and practises and take all necessary steps to ensure compliance with their obligations as flag States (Article 94(5)). In this regard, the role of IMO as the “competent international organization” in combating the challenges to regulate MASS becomes relevant. Even as IMO would be the organisation responsible for determining technical aspects to ensure safety and security in shipping, the jurisdictional issues and challenges to regulating MASS within the law of the sea framework require revising UNCLOS and domestic laws applicable to shipping regulation.

Therefore, amendments to existing laws or enacting new laws would be required to accommodate the particular characteristics and operational features of autonomous vessels. IMO has already finished the scoping exercise on MASS and reached a conclusion that the operation of MASS requires new international rules and standards to be set out (9). Furthermore, the Maritime Safety Committee and the Legal Committee of IMO have invited the State parties to submit proposals for the adoption of new rules and standards (10). In order to ensure compliance with existing laws and effectively monitor the operation of MASS, States may need to establish specific standards. In conclusion, it is suggested that Bangladesh, as a party to UNCLOS, should consider these challenges when adopting new regulations for MASS operations.

Dr Sabrina Hasan is a postdoctoral researcher at the East China University of Political Science and Law. Email: sabrinahasan22@gmail.com.

Recommended Citation: Sabrina Hasan, ‘Jurisdiction of Bangladesh over Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships: Challenges and Prospects,’ BCOLP Blog, July 2023.

Notes:

(1) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, 10 December 1982, 1833 UNTS 397 (entered into force Nov. 1, 1994).

(2) Robert Veal, Michael Tsimplis and Andrew Serdy, ‘The Legal Status and Operation of Unmanned Maritime Vehicles, (2019) 50 Ocean Development & International Law 23–48.

(3) Sabrina Hasan, ‘Analysing the definition of “ship” to facilitate Marine Autonomous Surface Ships as ship under the law of the sea’ (2022) Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, 1 (DOI: 10.1080/18366503.2022.2065115).

(4) Orkun Burak Öztürk, İdris Turna, ‘Investigation of ship radio communication deficiencies in port state controls: radio logbook records’ (2023) Australian Journal of Maritime & Ocean Affairs, 1-17.

(5) IMO Press Briefing, ‘IMO takes first step to address autonomous ships, Briefing: 08 25/05/2018,’ available at: http://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/Pages/08-MSC-99-MASSscoping.aspx.

(6) Aldo Chircop, ‘Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships in International LAW: New Challenges for the Regulation of International Navigation and Shipping’ (2019) 23 Cooperation and Engagement in the Asia-Pacific Region, 18-32, available at: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004412026_004; Dr Youri van Logchem, ‘International Law of the Sea and Autonomous Cargo “Vessels”, in Baris Soyer and Andrew Tettenborn (eds), Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Shipping: Developing the International Legal Framework, (Hart Publishing, 2021) 55.

(7) Professors Simon Baughen and Andrew Tettenborn, ‘International Regulation of Shipping and Unmanned Vessels,’ in Baris Soyer and Andrew Tettenborn (eds) Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Shipping: Developing the International Legal Framework (Hart Publishing, 2021) 13.

(8) Sabrina Hasan, ‘Marine Autonomous Ships in the Arctic: Prospects and Challenges’ (2021) 9 Current Developments in Arctic, 15-19, available at: http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fife2021120759218.

(9) International Maritime Organisation, ‘Autonomous Ships: Regulatory Scoping Exercise Completed’ (25 May 2021) available at: https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/pages/MASSRSE2021.aspx#:~:text=The%20Maritime%20Safety%20Committee%20%28MSC%29%20of%20the%20International,Maritime%20Autonomous%20Surface%20Ships%20%28MASS%29%20could%20be%20regulated.

(10) IMO (MSC), ‘Outcome of the Regulatory Scoping Exercise for the Use of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS)’, MSC.1/Circ.1638 (3 June 2021) available at: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/MSC.1-Circ.1638%20-%20Outcome%20Of%20The%20Regulatory%20Scoping%20ExerciseFor%20The%20Use%20Of%20Maritime%20Autonomous%20Surface%20Ships…%20(Secretariat).pdf; IMO (LEG) ‘Outcome Of The Regulatory Scoping Exercise and Gap Analysis of Conventions Emanating from the Legal Committee with Respect to Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS)’, Leg.1/Circ.11 (15 December 2021) available at: https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/MediaCentre/HotTopics/Documents/LEG.1-Circ.11%20-%20Outcome%20Of%20The%20Regulatory%20Scoping%20Exercise%20And%20Gap%20Analysis%20Of%20Conventions%20Emanating%20From…%20(Secretariat).pdf.